Let us start with first describing what Virtual Volumes is and what value it brings for an administrator.

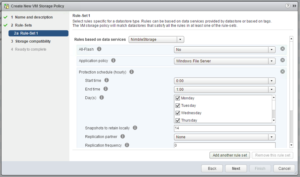

Virtual Volumes was developed to make your life (vSphere admin) and that of the storage administrator easier. This is done by providing a framework that enables the vSphere administrator to assign policies to virtual machines or virtual disks. In these policies capabilities of the storage array can be defined. These capabilities can be things like snapshotting, deduplication, raid-level, thin / thick provisioning etc. What is offered to the vSphere administrator is up to the Storage administrator, and of course up to what the storage system can offer to begin with. In the below screenshot we show an example for instance of some of the capabilities Nimble exposes through policy.

Figure 1 – Capabilities exposed by Nimble array

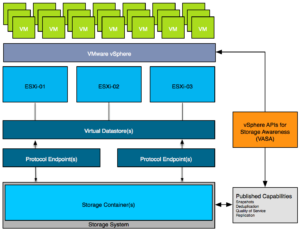

When a virtual machine is deployed and a policy is assigned then the storage system will enable certain functionality of the array based on what was specified in the policy. So no longer a need to assign capabilities to a LUN which holds many VMs, but rather a per VM or even per VMDK level control. So how does this work? Well lets take a look at an architectural diagram first.

Figure 2 – Virtual Volumes Architecture

The diagram shows a couple of components which are important in the VVol architecture. Lets list them out:

- Protocol Endpoints aka PE

- Virtual Datastore and a Storage Container

- Vendor Provider / VASA

- Policies

- Virtual Volumes

Lets take a look at all of these three in the above order. Protocol Endpoints, what are they?

Protocol Endpoints are literally the access point to your storage system. All IO to virtual volumes is proxied through a Protocol Endpoint and you can have 1 or more of these per storage system, if your storage system supports having multiple of course. (Implementations of different vendors will vary.) PEs are compatible with different protocols (FC, FCoE, iSCSI, NFS) and if you ask me that whole discussion with Virtual Volumes will come to an end. You could see a Protocol Endpoint as a “mount point” or a device, and yes they will count towards your maximum number of devices per host (256). (Virtual Volumes it self won’t count towards that!)

Next up is the Storage Container. This is the place where you store your virtual machines, or better said where your virtual volumes end up. The Storage Container is a storage system logical construct and is represented within vSphere as a “virtual datastore”. You need 1 per storage system, but you can have many when desired. To this Storage Container you can apply capabilities. So if you like your virtual volumes to be able to use array based snapshots then the storage administrator will need to assign that capability to the storage container. Note that a storage administrator can grow a storage container without even informing you. A storage container isn’t formatted with VMFS or anything like that, so you don’t need to increase the volume in order to use the space.

But how does vSphere know which container is capable of doing what? In order to discover a storage container and its capabilities we need to be able to talk to the storage system first. This is done through the vSphere APIs for Storage Awareness. You simply point vSphere to the Vendor Provider and the vendor provider will report to vSphere what’s available, this includes both the storage containers as well as the capabilities they possess. Note that a single Vendor Provider can be managing multiple storage systems which in its turn can have multiple storage containers with many capabilities. These vendor providers can also come in different flavours, for some storage systems it is part of their software but for others it will come as a virtual appliance that sits on top of vSphere.

Now that vSphere knows which systems there are, what containers are available with which capabilities you can start creating policies. These policies can be a combination of capabilities and will ultimately be assigned to virtual machines or virtual disks even. You can imagine that in some cases you would like Quality of Service enabled to ensure performance for a VM while in other cases it isn’t as relevant but you need to have a snapshot every hour. All of this is enabled through these policies. No longer will you be maintaining that spreadsheet with all your LUNs and which data service were enabled and what not, no you simply assign a policy. (Yes, a proper naming scheme will be helpful when defining policies.) When requirements change for a VM you don’t move the VM around, no you change the policy and the storage system will do what is required in order to make the VM (and its disks) compliant again with the policy. Not the VM really, but the Virtual Volumes.

Okay, those are the basics, now what about Virtual Volumes and vSphere HA. What changes when you are running Virtual Volumes, what do you need to keep in mind when running Virtual Volumes when it comes to HA?

First of all, let me mention this, in some cases storage vendors have designed a solution where the “vendor provider” isn’t designed in an HA fashion (VMware allows for Active/Active, Active/Standby or just “Active” as in a single instance). Make sure to validate what kind of implementation your storage vendor has, as the Vendor Provider needs to be available when powering on VMs. The following quote explains why:

When a Virtual Volume is created, it is not immediately accessible for IO. To Access Virtual Volumes, vSphere needs to issue a “Bind” operation to a VASA Provider (VP), which creates IO access point for a Virtual Volume on a Protocol Endpoint (PE) chosen by a VP. A single PE can be the IO access point for multiple Virtual Volumes. “Unbind” Operation will remove this IO access point for a given Virtual Volume.

That is the “Virtual Volumes” implementation aspect, but of course things have also changed from a vSphere HA point of view. No longer do we have VMFS or NFS datastores to store files on or use for heartbeating. What changes from that perspective. First of all a VM is carved up in different Virtual Volumes:

- VM Configuration

- Virtual Machine Disk’s

- Swap File

- Snapshot (if there are any)

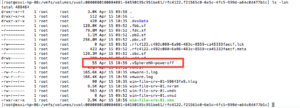

Besides these different types of objects, when vSphere HA is enabled there also is a volume used by vSphere HA and this volume will contain all the metadata which is normally stored under “/<root of datastore>/.vSphere-HA/<cluster-specific-directory>/” on regular VMFS. For each Fault Domain a separate folder will be created in this VVol as shown in the screenshot below.

Figure 3 – Single FDM cluster on VVol array

All VM related HA files which normally would be under the VM folder, like for instance the power-on file, heartbeat files and the protectedlist, are now stored in the VM Configuration VVol object. Conceptually speaking similar to regular VMFS, implementation wise however completely different.

Figure 4 – VVol FDM files

The power-off file however, which is used to indicate that a VM has been powered-off due to an isolation event, is not stored under the .vSphere-HA folder any longer, but is stored in the VM config VVol (in the UI exposed as the VVol VM folder) as shown in the screenshot below. The same applies for vSAN, where it is now stored in the VM Namespace object, and for traditional storage (NFS or VMFS) it is stored in the VM folder. This change was made when Virtual Volumes was introduced and done to keep the experience consistent across storage platforms.

Figure 5 – VVol based poweroff file

And that explains the differences between traditional storage systems using VMFS / NFS and new storage systems leveraging Virtual Volumes or even a full vSAN based solution.